The landscape of healthcare in Central Asia has been rapidly evolving since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, in particular, have embarked on ambitious journeys to reform their primary care systems. These reforms are critical steps toward achieving the elusive goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

I lived in Kazakhstan from 1994 – 1999 while working for the pharmaceutical company, Bristol-Myers Squibb. I participated in a few USAID sponsored health projects. During this period there were many ongoing studies on how to reform the healthcare sector, and many reforms in process.

In this article I wish to review the progress made, the challenges encountered, and what the future may hold for these nations on their winding path to providing comprehensive healthcare for all.

The Backdrop: Healthcare Under the Soviet Union

To fully appreciate the healthcare reforms undertaken in Central Asia, it is important to first understand the legacy Soviet healthcare system. During the Soviet era, the Semashko model was implemented, characterized by centralized planning and funding along with specialized care delivered through hospitals and polyclinics.

The Semashko Health Care Model in the Soviet Union

The Semashko model was the backbone of the Soviet healthcare system from its establishment in the 1920s until the fall of the USSR in 1991. Named after its founder Nikolai Semashko, this model had some notable achievements but also major inefficiencies.

Centralized Administration

- Healthcare was centrally administered by the USSR Ministry of Health in Moscow. They oversaw the system nationwide.

- Regional and municipal health departments executed policies and plans formulated centrally. They managed local infrastructure and personnel.

- Private medical practice was officially abolished, with all providers absorbed into the state system. This aimed to ensure standardized care.

Equal Access

- The Semashko model guaranteed free, universal healthcare for all citizens as a constitutional right. This was a remarkable achievement.

- However, access was not always equal. Nomenklatura elite and senior officials often got privileged treatment and access.

- Rural citizens typically had lower access to resources concentrated in urban centers. The system grappled with rural inequities.

Specialist-Oriented

- The system focused extensively on specialized hospital-based care and treatments. Polyclinics served largely as conduits to hospitals.

- Primary care physicians got less emphasis. Prevention and rehabilitation were underutilized too.

- Excessive specialization led to overuse of hospitals, inadequate chronic disease management, and high costs.

Public Health Focus

- The Semashko model had a strong public health focus – sanitation, immunization, workplace safety protocols etc. were strictly enforced.

- Mass mobilization campaigns expanded vaccination coverage and controlled infectious disease outbreaks effectively.

- However, health education and disease prevention were often neglected beyond campaigns.

Integrated Social Welfare

- Healthcare services were integrated into the broader socialist system alongside education, childcare, housing etc.

- But in practice, healthcare resources were often diluted across competing social priorities, undermining quality.

Infrastructure

- An extensive network of specialized, hierarchical hospitals from rural to republican level was established.

- Polyclinics served as an intermediate layer between patients and hospitals.

- In remote areas, feldsher health posts provided basic care but with limited capacity.

- Large industries ran dedicated workplace clinics and infirmaries for employees.

Financing and Control

- Healthcare was financed entirely through state budgets. No alternative insurance or private payment schemes existed.

- Strong central control led to inefficiencies in resource allocation, with little flexibility for local needs.

- Chronic underfunding left services under-resourced. Rationing of supplies and medicines was common.

Outcomes

- Life expectancy markedly increased, infectious diseases declined. Clear public health successes.

- Hospital utilization was often excessive and inefficient. Over-specialization persisted.

- The model was inflexible to needs and slow to innovate. Reforms were obstructed by rigid bureaucracy.

Thus the Semashko healthcare model, while achieving universal coverage, was plagued by systemic issues stemming from over-centralization, which catalyzed reforms after the USSR’s dissolution.

The Progress So Far: Reforming Central Asian Healthcare

Since gaining independence in 1991, the Central Asian republics have shown commendable dedication to overhauling their healthcare systems. The motivation has been clear: to transition away from the overly specialized and wasteful Soviet Semashko model towards a model aligned with the global priority of UHC.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines UHC as “ensuring that all people have access to needed health services of sufficient quality to be effective while also ensuring that the use of these sgervices does not expose the user to financial hardship.”

Some key features of reforms undertaken:

- Governance Reforms: Decentralization, autonomy for care providers.

- Service Delivery Reforms: Primary care strengthening, integration of polyclinics.

- Financing Reforms: Introduction of mandatory health insurance.

- Human Resources Reforms: Changes to medical education, pay structures.

These multi-faceted reforms aim to improve equity, efficiency, quality and financial protection. A detailed overview is presented in the article, “Primary care reforms in Central Asia – on the path to Universal Health Coverage”.

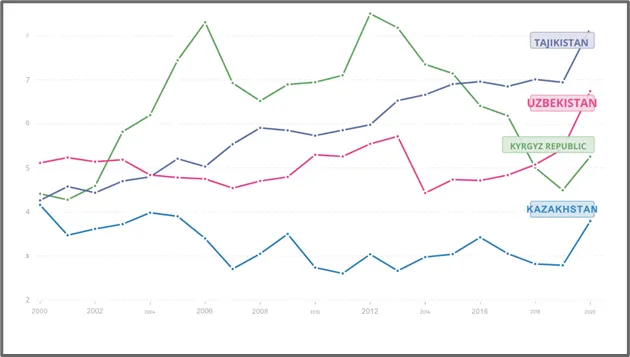

Table shows Healthcare spend as percent of GDP per country from 2000-2020

A Closer Look at Each Country’s Reform Journey

While the Central Asian republics faced similar legacies and challenges, each country charted its own path to reform. Let’s examine a few highlights:

Kazakhstan

- Polyclinics that previously operated as separate specialized units were consolidated into integrated health centers offering coordinated primary care. This improved continuity.

- Mandatory health insurance was introduced in 1996 to expand risk pooling. By 2017, over 80% of citizens were covered. However, benefit packages remained narrow.

- Health spending increased gradually from 2.3% of GDP in 1995 to 3.1% by 2017. But this remains below the 5% WHO target. Rural access disparities persist.

Kyrgyzstan

- A family medicine model with gatekeeping and enrollment was piloted from 1996 onwards. By 2015, over 90% of citizens voluntarily enrolled.

- The State Guaranteed Benefit Package launched in 1997 covered essential services. However, it excluded outpatient drugs which led to high OOP spending.

- Primary care physician numbers increased from 1,286 in 1995 to 2,658 by 2015. But distribution favors urban over rural areas.

Tajikistan

- Fragmented rural health centers and urban polyclinics were consolidated into integrated Primary Health Centers (PHCs) providing comprehensive care. However, human resource challenges undermine PHCs’ capabilities.

- Contracting introduced between PHCs and local health departments aimed to improve accountability. But implementation is uneven due to administrative bottlenecks.

- The National Health Strategy 2010-2020 provided strategic reform priorities. But funding limitations obstructed executing many priorities outlined.

Uzbekistan

- A family group practice model was implemented from 1996 onwards as a gatekeeping mechanism. However, referral compliance and roster enrollment have been suboptimal.

- Compulsory health insurance expanded risk pooling with over 60% coverage by 2015. But state funding remains dominant with insurance funds covering only 15% of total health spending.

- Health expenditures doubled from 2.2% to 4.5% of GDP during 1995-2015. However, the system remains underfunded for the reforms envisioned.

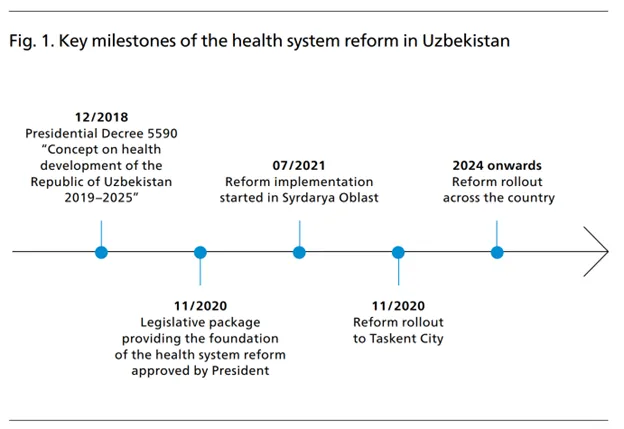

Key Health Reforms Implemented in Syrdarya Region, Uzbekistan

The Syrdarya region has spearheaded ambitious health sector reforms in Uzbekistan over the past few years. These systemic transformations aim to strengthen primary care delivery and integrate innovative health financing and digital tools.

Transforming Primary Health Care

- A State Health Insurance Fund was established as the single purchasing agency for health services and pharmaceuticals. This expanded risk pooling.

- Primary health care was reorganized into family physician teams and nurse health posts to improve access and coordination.

- Sophisticated e-health systems were implemented in all pharmacies to digitize supply chain management. This enhanced transparency.

Reforming Health Financing

- New provider payment mechanisms were introduced including per capita budgets and pay-for-performance contracts. This aimed to incentivize quality.

- Emphasis was placed on financial sustainability through improved revenue collection and cost controls. The region achieved a budget surplus within two years.

Adopting Digital Health Tools

- E-health systems were rolled out across the care continuum, integrating patient records, provider decisions, referrals and payments. This improved continuity and efficiency.

- Telemedicine infrastructure was established to extend specialist access to rural areas. Patient monitoring apps are being piloted.

Significance of These Reforms

As expressed by Dr. Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, Director of Health Systems and Public Health at WHO/Europe:

“The lessons learned in Syrdarya are a very promising start, and show us that achieving tangible benefits in other regions is possible.”

Syrdarya’s reforms demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of transforming service delivery, financing, and adopting digital health tools in Uzbekistan. The model provides a promising foundation for planned national scale-up of reforms to accelerate progress towards universal health coverage. These reforms are now being rolled out in Tashkent and then other regions of Uzbekistan.

While the commitment to reform is evident, implementing complex healthcare transformations has proven challenging for these nations emerging from Soviet legacies. Progress has been made, but systemic issues persist.

Persisting Challenges

Despite the reform momentum, several persistent challenges highlight the complexity of transforming these healthcare systems:

- Public Funding Shortfalls: There’s a significant gap in public funding for primary care across these nations. WHO recommends countries spend at least 5% of GDP on health, but currently, none of the Central Asian countries meet this threshold.

- Weak Financial Protection: Particularly concerning is the lack of coverage for outpatient medications in public benefits packages. On average, 35-60% of total health spending is out-of-pocket in these countries, exposing people to financial hardship.

- Low Compensation for Healthcare Workers: The low salaries and status of primary care workers are detrimental to both the quality of care and workforce retention. In Uzbekistan, a primary care doctor’s salary was just $110 per month in 2019.

- Rural Healthcare Access: Geographic barriers significantly hinder access to primary care in rural areas. In Tajikistan, 90% of healthcare infrastructure is concentrated in urban centers.

- Quality Monitoring Gaps: There’s an evident need for improved systems to monitor and enhance the quality of primary care. Clinical protocols are often outdated.

Reform Efforts in Primary Care Delivery

The reforms have been multi-faceted, focusing on integrating and optimizing primary healthcare delivery.

1. Family Group Practices

Central to this has been the merging of separate polyclinics into integrated family group practices. These provide comprehensive primary care services under one roof.

- Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have fully adopted this model.

- In Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, the integration is still in process.

2. Rural Primary Care

In rural areas, traditional standalone paramedic health posts have been adapted to better serve these communities through:

- Expanding the range of medical services offered.

- Integration into primary care networks.

- Telehealth access to urban specialists.

This has extended access to basic diagnostics and medications in remote regions.

3. Management Reforms

Additionally, management reforms have empowered primary care providers with greater budget and staffing autonomy, a move towards more efficient frontline service delivery.

The World Bank document on implementing health sector reform in Central Asia provides further insights into these reforms.

Financing and Resource Allocation Reforms

In an effort to redirect resources towards primary care and reduce access barriers, these countries have adopted new health financing models:

- Mandatory health insurance has been introduced in all four nations to pool risks and revenues. This now covers 64-90% of the population.

- State guaranteed benefit packages ensure a basic set of services are covered for citizens. However, the depth of coverage varies.

- Provider payment reforms have seen a shift from line-item budgets to case-based payments. This is meant to incentivize providers.

Despite these efforts, high out-of-pocket payments remain a huge issue, particularly for outpatient pharmaceuticals. The adoption of capitation-based provider payment methods is a step forward. However, the implementation challenges and their impact on efficiency cannot be overlooked.

The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies offers an in-depth look at Central Asian health financing reforms and issues in their report – Health Care Systems in Transition: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Medical Education Reforms

Transforming medical education has been central to strengthening primary care capabilities in Central Asia. Key aspects include:

- Family medicine residency programs were newly introduced in the 1990s to formally train primary care physicians. However, enrollment in these programs remains low.

- New competency-based curricula aim to align training with the needs of primary care delivery. But outdated pedagogies persist in practice.

- Interprofessional education has been piloted to promote collaborative practice. Yet this remains limited to select institutions and requires systemic integration.

- Rural immersion programs provide students exposure to remote healthcare settings. But incentives for graduates to then work in rural areas are lacking.

Persisting Challenges

- There is a shortfall of primary care physicians, as most graduates continue to specialize due to prestige and better salaries.

- In rural areas, 32-45% of family doctor positions remain vacant. This worsens healthcare disparities.

- The competencies of many active primary care doctors remain limited due to gaps in their original training.

- There is insufficient integration of public health into medical curricula to nurture prevention-oriented primary care practice.

Thus, while reform efforts have begun, truly transforming medical education requires systematic, multi-dimensional interventions. Bridging policy aspirations with on-ground implementation remains a key challenge. Sustained political commitment along with strong public-private partnerships will be critical for success.

For a deeper understanding of the scope of these medical education reforms, one can refer to a study published on PubMed.

Quality of Care and Access

Achieving universal high-quality primary care remains an elusive goal in Central Asia. Key challenges include:

- Suboptimal gatekeeping leads to inappropriate hospitalizations, incurring unnecessary costs and medicalization. Strengthening referral systems is needed.

- Outdated clinical protocols persist, with over 50% outdated in Tajikistan. This perpetuates ineffective treatments. A systemic review and update of guidelines is lacking.

- Fragmented care delivery hinders chronic disease management. Integrated care models are still developing.

- Medication stock-outs are common in rural areas due to forecasting and procurement issues. Reliable distribution chains are needed.

- Antiquated equipment particularly affects rural clinics. Modernizing medical technology requires major investments.

- Poor provider-patient engagement undermines disease prevention and health literacy. Patient-centered models are rare.

Reform Initiatives

- Clinical guidelines and treatment protocols are now being updated. But dissemination and uptake remain inconsistent.

- Integrated disease management programs for diabetes and hypertension are being piloted with variable success.

- Basic quality monitoring systems are being introduced. However, data utilization for improvements is limited.

Thus while quality reforms have been initiated, transforming service delivery on the ground remains at nascent stages. Impact is contingent on sustaining political will, aligning policies to implementation, and strengthening accountability. The path to universal access to quality primary care is still long and arduous.

The Roadmap for Health and Well-being in Central Asia 2022-2025, endorsed by ReliefWeb, emphasizes quality and prevention and can be accessed here.

Financial Protection: Reducing Out-of-Pocket Spending

As mentioned earlier, out-of-pocket spending accounts for 25-60% of total health expenditure in Central Asia. This exposes households to potential medical impoverishment. For example:

- In Uzbekistan, medicines constitute 50% of out-of-pocket spending.

- In Tajikistan, 10% of households face catastrophic healthcare costs.

- In Kazakhstan, voluntary health insurance covers just 1% of the population.

The need for more robust financial protection policies is clear. The Asian Development Bank’s publication – Central and West Asia Health Sector Approach 2025 – provides a comprehensive view of these challenges.

Human Resources for Health: Building an Empowered Workforce

Having an empowered and well-distributed health workforce is essential for effective primary care. But Central Asia grapples with some key issues:

- Persisting shortages of primary care professionals, especially in rural areas.

- Outflows of health workers due to low salaries, lack of career advancement, and unsatisfactory working conditions.

- Skill and competency gaps of primary care physicians due to insufficient training.

Tackling these issues requires interventions across the spectrum:

- Pre-service training: Increase student intake, expand family medicine education.

- In-service training: Regular skills upgrading of the workforce.

- Motivation: Better pay, recognition, rural recruitment schemes.

- Retention: Career progression pathways, improved infrastructure.

With comprehensive strategies, the needed health workforce can be developed to deliver universal primary care.

Looking Ahead: Future Reform Directions

While progress has been made, the Central Asian nations still face a winding and uphill journey to achieve universal health coverage. Some key future priorities include:

Governance

- Continue decentralization to the regional and district levels to improve responsiveness to local health needs. However, adequate central coordination and standards will remain important.

- Increase autonomy of health facilities over budgets, staffing, procurement and service delivery models. This needs to be balanced with robust accountability frameworks.

- Engage civil society and patient groups in oversight and participatory health planning to increase transparency. But bureaucratic resistance will need to be overcome.

Service Delivery

- Optimize the roles and coordination of primary care providers to improve prevention, screening, gatekeeping, and chronic disease management. Align incentives to strengthen team-based care.

- Integrate primary care with robust public health programs focused on addressing social and environmental health determinants,Communicable disease control, health promotion and literacy.

- Harness telehealth, m-health and data analytics to improve quality, optimize referral systems and strengthen rural service capabilities. Overcome interoperability challenges.

Health Financing

- Increase public spending on health incrementally from under 3% towards the WHO recommended 5% of GDP. Rationalize resources allocation towards cost-effective primary care.

- Expand State Guaranteed Benefit Packages, reducing out-of-pocket payments which lead to impoverishment. However, fiscal constraints persist.

- Develop strategic purchasing and innovative payment systems to incentivize quality and optimize provider performance. But capacity for design and implementation remains limited.

Health Workforce

- Increase investments in pre-service training for primary care providers – family physicians, nurses, midwives – with competencies aligned to community needs.

- Implement comprehensive retention strategies especially for rural areas – financial incentives, professional development, improved living conditions and infrastructure.

- Reform medical specialist training to nurture generalism, adaptability, and team-based approaches suited for primary care systems. Resistance from entrenched hierarchies will need to be managed.

Thus, while the road ahead is long, these reform priorities, if systematically implemented, can put the Central Asian nations firmly on the path towards universal health coverage.

The Role of Regional Cooperation

Regional partnerships and forums can play a key role in facilitating coordination and cross-country learning as the Central Asian nations undertake healthcare reforms.

The Central Asian Healthcare Partnership (CAHP) established in 2015 brings together representatives from health ministries, development agencies, and experts to collaborate on health priorities for the region. Some initiatives undertaken by CAHP include:

- Joint workshops to share best practices and lessons learned in implementing health financing reforms, improving rural access, reforming medical education etc. This helps avoid duplicative efforts.

- Multicountry studies to assess health systems performance and benchmark progress on indicators tied to universal health coverage.

- Developing regional strategic plans to control communicable diseases and achieve public health targets. These provide a framework for alignment.

- Collaboration on digital health and health information exchange to enable cross-border surveillance, telemedicine, and portability of health records.

- Partnerships to develop the specialized health workforce needed in areas like emergency medicine, cancer care, organ transplantation etc. where regional coordination is beneficial.

- Joint procurement mechanisms that aggregate demand across countries to improve affordability of vaccines, pharmaceuticals and medical equipment.

Thus regional cooperation platforms allow sharing of expertise, evidence, and resources to harmonize efforts and accelerate attainment of health goals. However, sustaining political commitment and overcoming bureaucratic resistance across nations remains challenging. Further integration through a Eurasian health pact could provide additional opportunities for synergies.

The Pace of Change

Transforming complex Soviet-era health systems is an iterative process. While the vision remains UHC, the countries are adopting a step-wise approach, assessing reforms and adapting along the way. Patience and persistence are key.

Oxford Academic’s article on “Lessons from two decades of health reform in Central Asia” and The National Academies Press’s chapter on “Health Reform in Russia and Central Asia” offer valuable insights into these future directions.

Conclusion

The journey of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan towards Universal Health Coverage has been complex, spanning over two decades since independence. While stubborn challenges remain, their commitment to transforming healthcare is commendable. With continued reforms, regional cooperation, and adaptive strategies, these Central Asian nations can build 21st century health systems and achieve the audacious goal of health for all.

#UniversalHealthCoverage, #PrimaryCare, #CentralAsia, #HealthReforms, #HealthcareAccess, #HealthFinancing, #MedicalEducation, #HealthWorkforce, #RegionalCooperation